Summary of Foundational Learning Theories

(scroll down for a Detailed Description of Learning Theories with citations)

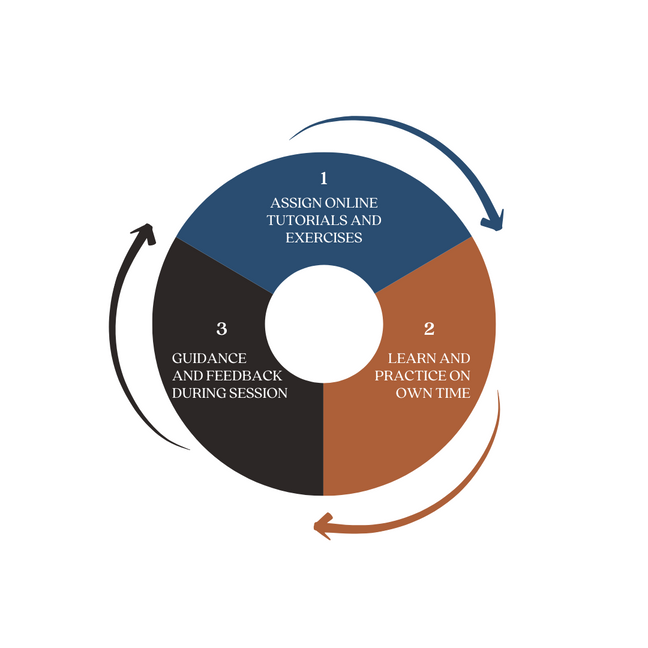

The following is a summary of learning and teaching practice founded on the most recent neurological and educational research and applied in the Practicing Musician curriculum, micro tutoring model, and professional development offerings.

- Cognitive Load Theory: Tasks are designed to consider the extent of cognitive processing involved in learning and the relationship of new learning to prior understandings.

- The Myth of Multi-tasking: Each micro-lesson is designed to focus on one concept or skill at a time and develop it across multiple micro-lessons and experiences within each lesson.

- Increased Saliency Theory: Content is intentionally designed to be obvious for students as to what is to be learned and why it is important to learn it.

- Brain-based learning theory: Lessons are designed to recycle learning that occurs in multiple ways while increasing difficulty, complexity, and contextual application.

- Spaced practice: is designed for thorough incremental lessons of study and restudy over time.

- Retrieval practice: The curriculum in the technology is designed in a spiral format intentionally revisiting concepts and skills across learning development to guide students toward developmental milestones as they implement continual improvement.

- Interleaving: Memory reconstruction is strengthened through knowledge, concepts, and skills being retaught in a variety of ways and in multiple contexts creating a web of interconnected memory traces.

- Elaboration: Each video lesson has intentionally designed ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions guiding the retention of knowledge, exploration of meaning, and development of conceptual connections.

- Dual coding theory: is accomplished in the technology through video modeling, verbal description, printed notation, verbal and typed feedback, and aural assessment of self and peer performance recordings.

- Retrieval practice: is built into the curriculum by applying former lessons directly into the enhanced complexity of the following lessons through the increased difficulty of musical pieces and opportunities to apply what has been learned in composing experiences and peer evaluations.

- Cognitive feedback: The technology provides feedback opportunities at each micro-lesson to guide students to set goals, take action to achieve their goals, and receive additional feedback related to actions within the context of the goal. Further development of the technology will enable self and peer assessment, which research suggests that giving students opportunities to assess their own learning results in greater academic gains and deeper reflection about the learning process.

Detailed Description of Learning Theories

Research on the process of learning and the educational practice that supports effective learning has greatly developed in the past 30 years. Neurological research and brain science have brought forth insights into how the brain attains, processes, stores, and retrieves information that can be defined as knowledge. But neurological research is not research on learning nor should it directly guide instructional practice. Problems arise when information from cognitive research is taken out of context and generalized without testing the construct in an educational setting. Evidence-based practice is a process used to review, analyze, and translate the latest scientific evidence. The following is a summary of educational research on learning and teaching practice that has been founded on the most recent neurological brain-based research and applied in the Practicing Musician curriculum and micro tutoring model.

- Cognitive Load Theory: refers to the amount of working memory resources used in the act of pursuing a learning goal. Since the brain can only do so many things at once, all Practicing Musician lessons are intentionally focused on what students are asked to do. Because short-term memory is limited, learning experiences are designed to reduce working memory ‘load’ to promote acquisition. For example, if a student is asked to critically examine a musical phrase (higher-order thinking) while also defining and ‘making sense of’ newly learned musical elements, this may be overloading short-term memory. Because the student doesn’t yet ‘understand’ the musical element, they would need to consistently access their short-term memory while processing the musical phrase. Foundational understandings must exist and be stored in long-term memory, so students can make sense of the new information. This construct for instruction is essential for learning. In summary, the more complex the task asked of students, the lower the capacity for students to attend to new information. That is why, in task development, we consider cognitive load and its relationship to prior learning important.

- The Myth of Multi-tasking: recognizes that it is nearly impossible for the brain to focus on more than one thing at a time. An important aspect with respect to student focus is when multiple tasks are presented the brain is going back and forth between two or more different tasks decreasing the efficiency of learning and reaction speed. To enhance learning, it is important for lessons to focus on a singular learning expectation and developmentally scaffold the learning experiences. Over time, these expectations can gradually increase in difficulty and complexity taking into consideration cognitive load. Each Practicing Musician micro-lesson is designed to focus on one concept or skill at a time and develop it across multiple micro-lessons and experiences within each lesson. (This is in contrast to many other curricular structures that present learning constructs simultaneously within a unit). It is important to recognize the broader construct of cognition that learning is not contained in isolated components of knowledge and skills, but must be learned by the students in the context of real-world application.

- Increased Saliency Theory: is an essential consideration for Practicing Musician because students pay attention to instructional materials they recognize as relevant or valuable. Saliency of content can come from many sources: the students’ own motivation, the situational interest (how engaging the information is presented), or even the ways that the students are expected to apply what is to be learned. In the case of Practicing Musician, situational interest is strengthened through applying the concept or skill taught to a performance of a musical piece, composing or improvising a new way to apply the skill, and analyzing and evaluating their own performance; all at their own speed and on their own time, cementing the knowledge obtained. In other words, it must be obvious to the students what is to be learned and why it is important to learn it.

- Brain-based learning theory: suggests that although memory is required in every activity, as soon as we learn something the brain immediately begins to forget it. What is currently known about memory is that it is not like a library, a computer, or a stored recording. Memory is reconstructive. When cognition is stored in long-term memory, the brain does not store how things were taught but how the learning experience was felt and understood across a variety of places in the brain (memory traces). Every time learning is retrieved, multiple memory traces are reconstructed (put together) with whatever other memory traces that seem to connect. Most often what is recalled is altered from its original form. Thus, it is essential to teach content, concepts, and skills multiple times in multiple ways and to confirm students recognize the connection to solidify long-term learning. Practicing Musician lessons are designed to recycle learning that occurs in multiple ways while increasing difficulty, complexity, and contextual application – not by mere repetition but by reconfiguring examples and engaging the imagination to satisfy the desire for proficiency.

- Brain-based instructional strategies: Researchers have made significant advances in applying cognitive processes to education.

- Spaced practice: is designed through incremental lessons of study and restudy over time. Practicing Musician is designed to sequence short lessons that build upon each other. The micro tutoring model is designed to guide and motivate students toward increased achievement over time as well as boost storage and retrieval strength.

- Retrieval practice: involves bringing information to mind from memory (reconstructing memory traces), a technique that promotes long-term memory. The curriculum in the technology is designed in a spiral format intentionally revisiting concepts and skills across learning development with increasing difficulty and complexity. The micro tutoring model that aligns with the curricular-designed retrieval practice guides students toward developmental milestones as they progress toward continual improvement.

- Interleaving: involves switching between content and learning problems rather than studying one thing for too long. Working through developmental understanding and skills across time encourages increased cognitive discrimination. Across a series of lessons, concepts are addressed in multiple ways through a variety of musical exercises and pieces with increased difficulty and complexity. Some research suggests that it takes 12 to 20 repetitions to assure long-term retention and accurate reconstruction during recall. Utilizing varied content in contrast to direct repetition leads to enhanced learning. Neurological research has discovered that memory reconstruction is strengthened when knowledge, concepts, and skills are retaught in a variety of ways and in multiple contexts creating a web of interconnected memory traces. This web of synaptic connections enables retrieval in multiple contexts. With Practicing Musician, student progress is recorded for self, peer, and teacher feedback, thus enhancing multiple representations of learning. In addition, assessment rubrics offer guidance on learning needs as well as reinforcement of progress.

- Elaboration: is thought to be one of the best ways to increase learning and memory. This involves students asking and attempting to answer ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, which assists students in grasping and understanding abstract ideas and concepts. As a tested educational process, it is a means for adding features to student memory traces to enhance retrieval. Each video lesson has intentionally designed questions guiding the retention of knowledge, exploration of meaning, and development of conceptual connections. Within the broader micro-lesson, opportunities are infused for student self-interrogation and elaboration of the learned constructs.

- Dual coding theory: is founded upon neurology and cognitive learning research focused on combining verbal, text-based, and visual materials in the process of instruction because it enhances learning through the brain processes and stores each modality as a separate memory trace. Research suggests that when the multiple modalities of content presentation are connected in a meaningful way, these multiple forms of representation can produce deeper learning. This is accomplished in the technology through video modeling, verbal description, printed notation, verbal and typed feedback, and aural assessment of performance – all at a speed comprehensible by the student to stimulate greater subjective engagement.

- Retrieval practice: is thought to strengthen memory, making information more retrievable later when needed in future rehearsals and with new pieces/styles of music. Every time a memory is recalled, multiple memory traces are reconstructed and reinforced. When students are asked to remember and apply formerly learned knowledge, concepts, and skills, they’re not just checking their memory, they are enhancing it. This means that when students bring information to mind, they are changing their memory and making it more flexible for future use. Even without external feedback, retrieval practice gives students feedback on what they know and do not know. Teacher feedback provides guidance in the enhancement of memory. Retrieval practice is built into the curriculum by applying former lessons directly into the enhanced complexity of the following lessons through the increased difficulty of musical pieces and opportunities to apply what has been learned in composing experiences and peer evaluations. The theory of retrieval-based Learning (recall, review, recall) allows students to learn from feedback, apply the learning, and recall again via scaffolded learning.

- Cognitive feedback: is feedback provided through prompts, cues, and questions that help learners reflect on the quality of the learning that they construct. Recent research supports the notion that providing students with meaningful feedback can greatly enhance their learning and achievement. Feedback is a critical component in improving performance. Feedback provides increased cognitive schemas to improve future learning and performance. It can help students improve confidence, self-awareness, and motivation for learning. Yet not all forms of feedback are equally effective, and some feedback can even be counterproductive — especially if it is delivered in a solely negative or corrective way. The tutorial processes provide enhanced opportunities for direct and timely feedback. The more personalized the feedback is, the better it will be received. Tutors are guided to provide specific, student-centered feedback: (1) delivered to students individually; (2) about their performance; and (3) presented in a motivation-building way. Numerous studies indicate that feedback is most effective when it is provided immediately versus a few days, weeks, or months later. The tutorial processes in this technology provide the opportunity for feedback at each micro-lesson. A prerequisite for effective feedback is that an individual has a goal, takes action to achieve that goal, and receives feedback related to these actions within the context of this goal. Researchers largely agree that impactful feedback is most often directed towards a specific goal that students are (or should be) working to achieve. Further development of the technology will enable self and peer assessment, which research suggests that giving students opportunities to assess their own learning results in greater academic gains and deeper reflection about the learning process.

- Assessment of Learning: is based upon the construct that presenting information and demonstrating how a skill is performed does not necessarily reflect the learning that will result. Assessments through which students demonstrate learning are focused upon how a student understands and demonstrates their learning instead of a recognition of what has been taught. It is important to recognize in the technology that there are various forms of knowledge and skills:

Types of Knowledge

- Content knowledge: recall of content and connections made to prior held knowledge

- Contextual knowledge: recognition of how knowledge fits into specific contexts (social, cultural, emotional, etc.)

- Procedural knowledge: a transfer of cognitive knowledge into the application or knowing how to use knowledge in a combination of cognitive and psychomotor awareness

- Meta-cognitive knowledge: a student’s awareness of what they know or don’t know

Types of Skills

- Competency Skills: Sections attained to pre-determined levels of achievement.

- Process Skills: A series of actions or steps taken in order to achieve a particular end.

- Cognitive Skills: any of the mental functions assumed to be involved in the application, interpretation, and transformation of the individual.

References

Ansari, D., Coch, D., & De Smedt, B. (2011). Connecting education and cognitive neuroscience: Where will the journey take us? Educational philosophy and Theory, 43, 37-42.

Chandler, P. & Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive Load Theory and the format of instruction. Cognition & Instruction, 8, 293-240.

Dekker, S., Lee, N.C., Howard-Jones, P., & Jolles, J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: Prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 3.

Dunder, S., & Gundiuz, N. (2016). Misconceptions regarding the brain: The neuromyths of preservice teachers. Mind, Brain, and Education, 10, 212-232.

Dunloskky, Rawson, Marsh, Nathan, & Willingham (2013)

Gathercole, S. E., Pickering, S. J., Knight, C., & Stegmann, Z. (2004). Working memory skills and educational attainment: Evidence from national curriculum assessment at 7 and 14 years of age. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 18, 1-16.

Gopher, D., Armony, L., & Greenshpan, Y. (2000). Switching tasks and attention policies. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129, 308-339.

Gore, J. M., & Gitlin, A. D. (2004). Visioning the academic-teacher divide: Power and knowledge in the educational community. Teachers and Teaching, 10, 35-38.

Guzzetti, B. J. (2006). Neuroscience and education: From research to practice? Nature review Neuroscience, 7, 406-413.

Hidi, S. and Harackiewicz, J. M. (2000). Motivating the adademically unmotivated: A critical issue for the 21st century. Review of Educational Research, 70, 151-179.

Kang, S. H. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning. Policy Insights from the Behavior and Brain Sciences, 2, 12-19.

Lavie,N., Hirst, A., De Fockert, J.W., & Viding, E. (2004). Load theory of selective attention and cognitive control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133, 339-354.

Paivio, A. (2007). Mind and its evolution: A dual coding theoretical approach. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pashler, H., Bain, P. M., Bottge, G. A., Graesser, A., Koedinger, K., McCaniel, M., & Metcalfe, J. (2007). Organizing instruction and study fo improve student learning: IES practice guide. Washington DC, USA: National Center for Educational Research, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education.

Pomerance, L., Greenberg, J., & Walsh, K. (2016, January). Learning about learning:What every teacher needs to know [Report]. Retrieved from www.nctq.org/dmsView/Learning_About_Learning_Report

Roediger III, H. L. (2013). Applying cognitive psychology to education: Translational educational science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14, 1-3.

Roediger, H. L., Putnam, A. L. & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten benefits of testing and their applications for educational practice. In J. Nestre & B. Ross (Eds.) Psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education (pp 1-36). Oxford: Elsevier.

Schacter, D. L. (2015). Memory: An adaptive constructive process. In D Nikulin (Ed.), Memory in recollection itself. New York: Oxford University Press.

Simmons, A. L. (2012). Distributed practice and procedural memory consolidation in musicians’ skill learning. Journal of Research in Music Education, 59, 357-368.

Sparrow, B., Liu, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Google effects on memory: Cognitive consequences of having information at your fingertips. Science, 333(6043), 776-778.

Wang, Z. & Duff, B. R. (2016). All loads are not equal: Distinct influences of perceptual load and cognitive load on peripheral ad processing. Media Psychology, 19, 589-613.

Weinstein, Y & Sumeracki, M. (2019). Understanding how we learn: A visual guide. Routledge Publishing. New York, NY.

Weinstein, Y., Madan, C. R., & Sumeracki, M. A. (2018). Teaching the science of learning